|

| |

| |

|

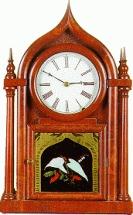

(Below): Reversed curve clock, by Brewster and Son, Conneticut, c. 1855

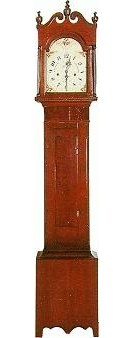

(Below): American tall clock by Luman Watson, Cincinnati, c. 1825.

(Below): Sharp Gothic clock by Brewster and Ingrahams, c. 1845. and Round Gothic clock by Brewster Manufacturing Company, c. 1845.

|

Before the revolution of 1776, Americans were accustomed to buying manufactured goods from Europe, especially England, but political differences and the Napoleonic wars disrupted this trade so that by the beginning of the nineteenth century, home grown industries were developing by necessity. Clocks were made in the traditional manner in small workshops and their design largely mirrored English styles. The transformation of clockmaking from a craft to an industry, occurred in 1807 with the opening of Eli Terry's Ireland clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut. Water-powered machinery turned out 4,000 wooden tall clock (longcase) movements in three years, the first horological production line in the world. The tall clock by Luman Watson of Cincinnati was similarly produced. Tall clock movements are difficult to transport over long distances because of their weights and long pendulum. This became a factor in the changing design of Connecticut clocks, as the country rapidly expanded westwards. Smaller shelf clocks like the Samuel Terry example began to be made after 1810 but these continued to be weight-driven with wooden movements. As brass began to be manufactured the gradual switch from wood gathered pace. The difficulty of producing coiled steel springs - essential for the light-weight and portability of clocks - led to ingenious solutions like joseph Ives' wagon spring clock, the motive force coming from a leaf spring bolted to the floor of the case. Brass springs were also used by companies such as Brewster despite the unsuitability of this material, and it was not until 1847 that steel was adapted for this purpose in America. In 1842, Connecticut clock production had outstripped home demand and jerome began to export thousands of clocks to Europe with dire consequences for the British industry. During the 1850s the dozens of small Connecticut companies amalgamated to become seven giants. These were Ansonia, New Haven, Waterbury, Seth Thomas, Ingraham, Gilbert, and Welch. All these companies were to survive into the twentieth century but the effects of the Depression of the 30s rising costs and foreign competition proved fatal and between 1929 and 1967 they all ceased trading. |