|

| |

| |

(Above): Gilt tabernacle clock by A. Meyer, Augsburg, c. 1600.  (Above): Gilt horizontal table clock, Augsburg, maker unknown, c. 1600. |

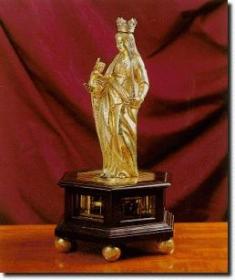

During the period of the late Renaissance, from the sixteenth to the early seventeenth centuries, one of the largest centres of clock manufacturing in Europe was in Augsburg, Bavaria. The making of large public clocks derived directly from the work of blacksmiths, but as the demand for domestic timekeepers increased, the established profession of clockmaking evolved more from the armourer and locksmith.  (Above): Gilt tinder box alarm clock by Maurer of Berlin, 1750. It is no surprise that Augsburg established itself as the premier horological centre of Europe; already renowned for the metal crafts, it was close to the major mining areas of Europe. Augsburg's central geographical position and its political links across Europe through the vast Holy Roman Empire, all helped to consolidate its economic supremacy. The foundation of the Clockmakers Guild around 1550 further helped to develop the industry and maintain the highest standards. The gilded opulence of the Augsburg clock reflects the exuberance of the High Renaissance. The simplest style is the horizontal table clock in a drum or octagonal case, while the more extravagant tabernacle clock has-two or three dials, the case surmounted with a tiered rotunda containing one or two bells for hour and quarter-hour striking. With one exception, all the examples in the museum have had the original movement converted at a later date, for improved timekeeping. Augsburg was at the centre of the counter-Reformation, and the images of Catholic Christendom are frequently found in clocks made there. Examples include the Virgin Mary, whose crown revolves to record the quarter hours, and the crucifix clocks with revolving globes measuring the hours in digital fashion. Many clockmakers specialised in automata mechanisms, some of which are legendary in their complexity. The museum collection includes examples of the simpler kind. The lion clock has eyes that move with the ticking and a mouth that opens and shuts as the clock strikes. Those with a macabre sense of humour will appreciate the crucifix clock with skull and crossbones at the base of the cross; as the clock strikes, the skull chatters its teeth! Before an Augsburg clockmaker was accepted into the ranks of the master craftsmen, he had to make a masterpiece clock. These staggeringly complex mechanisms included an astrolabe dial, astrological symbols and a dial of the saints days throughout the year. The Thirty Years War (1618-48) ended Augsburg's reign as a major horological centre. During this religious conflict, the city was besieged and sacked, and as much as half of its population perished. Before Augsburg's former position could be recovered, it had been overtaken by London as the premier clockmaking centre of the world. (Below): Madonna clock by Jeremias Pfaff, Augsburg, c. 1600.

|